World War II Chronicle: February 1, 1941

Click here to read TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

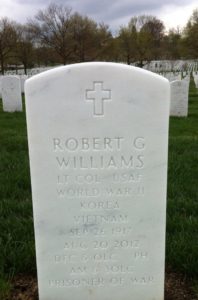

A bulletin reports on the front page that Maj. Robert Williams is the first American observer injured during the Luftwaffe’s bombing campaign (see April 2’s Chronicle for more). Surely there are dozens of Robert Johnsons who served during World War II — there are 84 men of that name buried at Arlington National Cemetery alone — and it would be difficult to determine 80 years after the fact which was the casualty. But often you can find equally interesting search results, if not more interesting, than what you originally set out to find out.

Somewhere in this picture of fighter pilots is a Maj. Robert G. “Digger” Williams. The American Air Museum states that he began flight training as an aviation cadet at Naval Air Station Pensacola in 1938, then enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1940. We don’t know whether he completed his training in the United States, or if he deserted to join the RCAF, but we do know that he was commissioned a Sergeant Pilot in October of 1941 (we can therefore determine this isn’t the Maj. Johnson reported as wounded in the paper).

Williams transferred to the Royal Air Force, flying 33 combat missions as a Spitfire pilot with the No. 611 Fighter Squadron. In 1942 he started flying for the United States Army Air Force. On March 21, 1944, Johnson — now a veteran of 137 combat missions — was leading a squadron of P-51 pilots on a strafing mission targeting enemy airfields in the Bordeaux region of France when he developed a coolant leak. He crashed and was captured by the Germans. Resisting interrogation efforts, he landed in Stalag Luft I on the Baltic Sea where he spent the remainder of the war.

After 28 years of service, Lt. Col. Johnson retired from the U.S. Air Force — his fourth branch of service — in 1970. He had earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses and four Air Medals for Valor. He passed away peacefully in 2012 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Williams served four different services, but another officer I ran across this morning served in five, and all were American. Lt. Gen. William E. Kepner joined the Marine Corps (1) in 1909, and after his hitch was up, became a lieutenant in the Indiana National Guard (2). During World War I he held an infantry commission in the U.S. Army (3), serving as company commander at Chateau-Thiery, then led the 4th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion during the Meuse-Argonne offensive. He also fought at Aisne, Champagne, Marne, and St. Mihel, earning a Distinguished Service Cross for leading a patrol that eliminated a German machinegun position in hand-to-hand combat.

After the war, Kepner got into balloons and airships, and was part of the three-man Army Air Corps (4) crew that rode a balloon above 60,000 feet in 1934. During World War II he again led from the front, flying 24 combat missions in bombers and fighters while commanding the Eighth Air Force’s 2d Bomb Wing and then the Ninth Air Force.

Following the war Kepner led 12th Tactical Air Command and the U.S. Air Force (5) Alaska Command before retiring in 1953. He held six ratings during his diverse career: command pilot, combat observer, senior balloon pilot, zeppelin pilot, semi-rigid pilot, and metal-clad airship pilot… Not bad for a former gyrene.

The Firstest, the Longest and the Mostest

Also, the lone colonel in the photograph above is Donald M.J. Blakeslee. Like Williams, Blakeslee also left the United States to fly for the Canadians, compiling 200 hours with the RCAF’s No. 401 Squadron before volunteering to command the No. 133 Eagle Squadron. By war’s end, Blakeslee was a double ace, flew the first P-51 Mustang over Berlin, and had flown more than 1,000 hours on over 500 combat missions — more than any American pilot during the war. During World War II he earned two Distinguished Service Crosses, seven Distinguished Flying Crosses, two Silver Stars, six Air Medals and the British Distinguished Flying Cross. During Korea, he received the Legion of Merit, another Distinguished Flying Cross and four Air Medals.

Incidentally, the picture of the pilots during a briefing above is of Blakeslee’s 4th Fighter Group. The 4th was composed of former Royal Air Force Eagle Squadrons (the 71st, 121st, and 133rd) and initially flew Spitfires before transitioning to P-47 Thunderbolts, and later, P-51 Mustangs. The 4th FG destroyed 1,020 German planes during the war, including a record-setting 31 victories in a day on April 11, 1944. The picture with Eisenhower and Doolittle was taken during an awards ceremony where Eisenhower would present Blakeslee with the first of his two Distinguished Service Crosses of the war. He retired as a colonel in 1965.

Blakeslee took over as 4th FG’s commanding officer from Col. Chesley G. Peterson, whom we discuss here.

Fort Lewis soldiers are pictured on page three test-firing new M1 75mm pack howitzers, so-named as the gun could be broken down for transport by pack animals… Effective today the U.S. Fleet has been split into three separate components: Atlantic Fleet (LANTFLT), Pacific Fleet (PACFLT), and Asiatic Fleet… Page nine reports that Adm. Husband E. Kimmel relieved Adm. James O. Richardson as Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet (CINCUS). Kimmel will also serve as CINCPAC, Adm. Ernest J. King as CINCLANT, and Adm. Thomas C. Hart remains in charge of the Asiatic Fleet. Until today, CINCUS commanded both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets, technically named Scouting Force and Battle Force, respectively. Richardson was considered the Navy’s foremost authority on Japanese war strategy, and he protested Pres. Roosevelt’s 1940 decision to move the Pacific fleet’s headquarters from San Diego to Pearl Harbor (leading to his removal as CINCUS), feeling it would leave our ships vulnerable to attack and was of little practical value to foreign policy… Sports section begins on page 18

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 1 February 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-02-01/ed-1/