World War II Chronicle: May 11, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

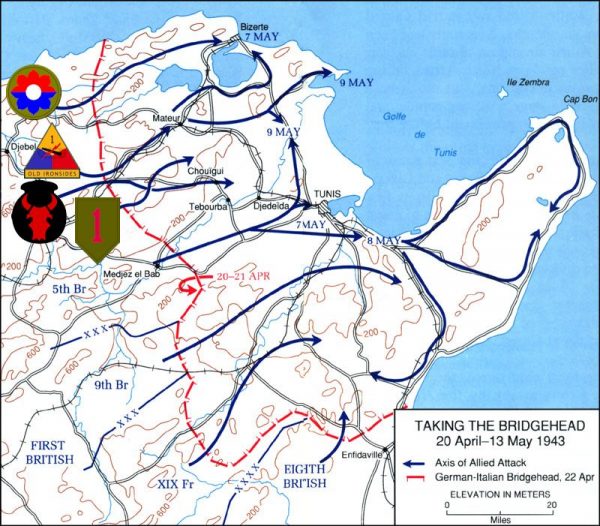

Rommel’s Afrikakorps look as though they may be facing a Dunkirk of their own as the Tunisian campaign draws to a close. Maj. Gen. Omar Bradley’s II Corps mans the Allied left flank. Bradley leads a contingent of French and Moroccan troops, in addition to:

- 1st Armored Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Earnest N. Harmon

- 1st Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Terry de la Mesa Allen

- 9th Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy

- 34th Infantry Division, Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder

When II Corps sailed to England they were led by Mark Clark. He passed the torch to Lloyd R. Fredendall prior to the TORCH invasion, who was sacked after the Battle of Kasserine Pass and replaced by George Patton in March. The Americans fought well under Patton, who departed for Casablanca in April to help plan the next major operation. Bradley took over as II Corps’ commanding general when Patton departed…

Although he is not mentioned in the paper it is worth noting that Lt. Col. William C. Westmoreland commands the 9th Infantry’s 34th Field Artillery Battalion. Westmoreland was the top cadet in his class at West Point in 1936 and will one day become Chief of Staff of the United States Army… George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… Sports section begins on page 16… The “Torpedo 8” story continues on page 34

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

NORTHERN TUNISIA — Just after daylight on the first morning of battle that I recently sat in on as an awed semi-participant, wounded men and German prisoners began coming back down the hill to us.

They didn’t have far to come — the less seriously wounded could walk down in five minutes. We were that close.

About an hour after daylight I noticed that a man on one of the stretchers coming toward us had on a British officer’s cap. I had a hunch, and ran over to look closely. Sure enough, it was my tentmate of the previous three nights — a British captain.

When I ran up, the litter bearers put down the stretcher, and I kneeled down beside it. As I did so the Captain opened his eyes. He smiled and said, “Oh, hello, hello. I was worrying about you. Are you all right?”

How’s that for British breeding?

I started to say something about being sorry, but before I could get a word out he said:

“Oh, it’s nothing at all, absolutely nothing. Just a little flesh wound. It isn’t as though I’d been hit in the spine or anything.”

But the Captain had a big hole in his back, and his left arm was almost shot up. They had given him morphine and he wasn’t in much pain. his shirt was off, but he still wore his pistol and his cap as he lay. There was blood all over his undershirt. His tanned face had a pale look, but his expression was the same as usual.

Our first-aid station was too much under fire for ambulances or any vehicles to be brought up, so four litter-bearers still had to carry the Captain a mile and a half back to the rear. When he heard this he said: “That’s perfectly ridiculous, carrying me that far. They’ll do no such thing. I can walk back.”

The doctor said no, it would start him bleeding again if he got up. But the Captain got halfway off the litter and I had to give him a push and a few cusswords before he would consent to being carried.

The Captain was a young fellow, sort of pugilistic-looking but with a gentle manner and an Oxford accent. He had been in the British Eighth Army two years without getting hurt. He had just joined us as a liaison officer, and was shot in the first half-hour of his first battle.

We’d had nice talks in our tent about England and the war and everything. It seemed impossible that some one I’d known and liked and who had seemed so whole and hearty such a few hours before could now be torn and helpless. But there he was.

A few minutes later two German prisoners came down the hill, with a doughboy behind them making dangerous motions at their behinds with his bayonet.

The captor was a straight American of the drawling hillbilly type, who talked through his nose. I’m sorry I didn’t get his name. When he walked the Germans back to his sergeant he said, in his tobacco-patch twang:

“Hey Sarge, here’s two uv Hitler’s supermen fer yuh.”

The two prisoners were young and looked very well fed. Their uniforms were loose-fitting khaki, sort of like men’s beach suits at home. With their guns and all their other soldier gear taken away, they had the appearance of being half-dressed. The expression on their faces was one of wondering what came next.

They were turned over to another soldier, who marched them across the fields to the rear. I couldn’t help grinning as I watched, for the new guardian stayed well behind them and walked as though he were treading on ice.

Our aid station was merely a formation of outcropping rocks on the hillside. The wounded all stopped there to await new litter-bearers to carry them back.

The battalion surgeon, Capt. Robert Peterman, of Hicksville, L.I., had remarked earlier how our wounded never groaned or made a fuss when they came in, so I paid special attention. And it is true that they just lie on their stretchers, docile and patient, waiting for the medics to do whatever they can.

Some of them had been given morphine and they were dopey. Some smoked and talked as though nothing much had happened. A good many had been hit in their behind by flying fragments from shells. The medics there on the battlefield would either cut the seat out of their trousers or else slide their pants down, to treat the wounds, and they’d be put on stretchers that way, lying face down. It was almost funny to see so many men coming down the hill with the white skin of their behinds gleaming against the dark background of brown uniforms and green grass.

Some of the boys who were not too badly wounded seemed to have an expression of relief on their faces. I know how they felt, and I don’t blame them.

I remember from the last war the famous English phrase of “going back to Blighty” — meaning being evacuated to England because of wounds. In this war we have a different expression for the same thing. It is “catching the white boat,” meaning the white hospital ship that takes wounded men back across the Atlantic.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 11 May 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-05-11/ed-1/