Day of Infamy: What happened to the eight sets of brothers on USS OKLAHOMA

When the battleship USS Oklahoma turned over just 15 minutes after being hit by the first Japanese torpedo on 7 December 1941, 429 sailors and Marines were either already dead — or soon would be. Men that somehow survived the initial nightmare of torpedoes, bombs, shrapnel, bullets, and fire had to swim through another level of hell to reach the relative safety of land. Those that remained inside the flooding ship would spend days in pitch-black darkness with no food, water, and what breathable air they had was being slowly used up while they hoped for rescue.

78 years later, we can’t possibly comprehend what those men endured that day. For a few sailors, however, they were concerned not only with their own welfare, but with that of their brothers as well: Among the battleship’s crew of 1,300 were eight sets of brothers. Here are their stories.

20-year-old Charles Casto and his 19-year-old brother Richard, of East Liverpool, Ohio both perished. Richard’s body was found and buried after the attacks at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, but Charles was interred among hundreds of other USS Oklahoma unknown sailors and Marines. In 2017 the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency identified Charles’ remains, which had been buried with other unknowns in a group grave, and reinterred him alongside his brother.

Seaman 1st Class Kirby R. Stapleton (24, of Chillicothe, Mo.) was trapped below decks when the torpedoes tore open the battleship. His brother Delbert was topside and survived. Kirby’s remains were identified in 2018 and buried alongside Delbert, who passed away in 2001, at the Riverside (Calif.) National Cemetery.

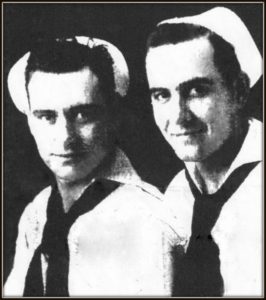

The Blitz Twins — Machinist’s Mate 2nd Class Leo and Fireman 1st Class Rudolph — had joined the Navy at 17 and nearing the end of their enlistment when Japanese planes targeted their ship. Rudolph had patrol duty topside and reportedly went below to help Leo, who was working on a generator, once the ship started sinking. Neither survived.

The remains of the 20-year-old sailors from Lincoln, Neb. were identified in May of 2019 and laid to rest.

21-year-old James Headington from Bay City, Mich. had shore leave on Sunday morning and was powerless to save his younger brother Robert, who was killed. James passed away in 2006, having also served during the Korean War. Robert’s remains were identified in 2018 and interred in Arlington National Cemetery.

Richard “Swede” Atley joined the Navy after graduating high school, wanting to serve alongside his brother aboard the Oklahoma. The Navy granted his request and he transferred over on 7 December 1940. One year later, Atley was among 32 sailors lucky enough to be rescued after being trapped inside for 36 terrifying hours. He was never able to locate his brother, Quartermaster 2nd Class Daryle Artley (21, of Maywood, Neb.). Richard served in the Navy until 1946 and passed away in 2011.

Daniel Boone Goodwin joined the Oklahoma crew in 1935 and was enjoying leave with his wife when the Japanese attacked. By the time he reached the scene, his ship was already underwater, having claimed the life of his younger brother Clifford (24, of Diamond, Mo.), who worked on the lowest deck of the battleship. Daniel passed away in 1988 and his brother’s remains were identified 30 years later.

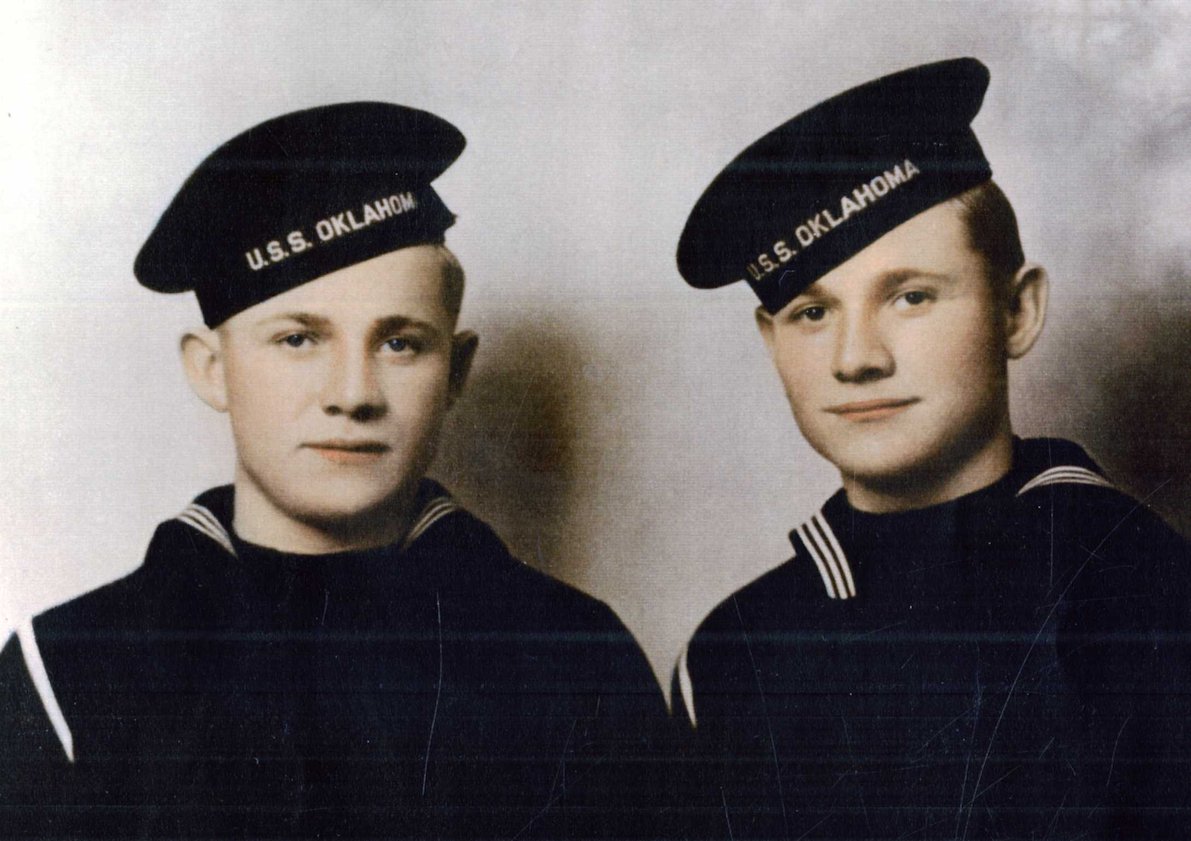

The Barber Brothers — Malcolm (22), LeRoy (21), and Randolph (19) — all enlisted in 1940 and served together as firemen. On 5 December, the brothers had this photograph taken of them and sent it along with Christmas presents to their family in New London, Wisc. Shortly after receiving the package, their parents were informed that all three were listed as missing and likely killed.

Their bodies were never recovered. The Buckley-class destroyer escort, USS Barber (DE-161), was named in their honor.

Paul Steen was in the battleship’s hold when the attacks began and was trapped. The only way out of the doomed warship was through a small porthole. He was one of a dozen sailors who were assisted to safety Lt. (j.g.) Aloysius Schmitt, who became the first chaplain killed in World War II. Brother Harold reported for duty early that morning — possibly saving his life — and was attempting to return fire against the hostile warplanes when the abandon ship order was given.

The brothers both managed to navigate the flaming oil-coated waters as Japanese planes strafed the survivors. It would be several days before they realized the other had lived.

Several of these brothers had additional family members who served during World War II. Steen: younger brothers Bobby and Jack also served as sailors once they reached enlistment age; Goodwin: three other brothers also served; Stapleton: older brother Glenn also served in the Navy during World War II; Casto: Orville was a private first class in the Army and Oscar was a master sergeant in the Air Force — also serving during Korea; Blitz: Father Henry Blitz Sr. emigrated to the United States after receiving his discharge from the Russian army. Stepsons Reinhold Rebensdorf served as a Navy Seabee on Pearl Harbor and Peter Rebensdorf was in the Army for nine years.