World War II Chronicle: April 18, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

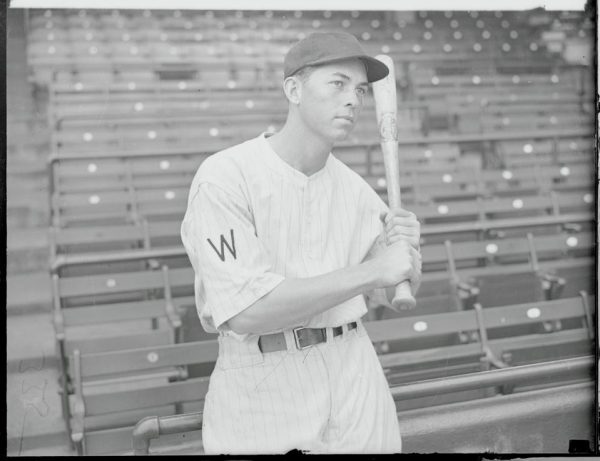

The front page reports that Washington Senators shortstop Cecil Travis has been designated Class 1-A. Modern readers may think that means the shortstop has been sent to the minors for a rehab assignment or something, but in 1941, that meant available for immediate service in the U.S. Armed Forces. To make matters worse, this comes just two days after right fielder Buddy Lewis got his draft notice. Tough luck for Washington fans, who haven’t experienced a winning season since 1936, to see what talent you do have get siphoned off by the war.

Travis isn’t called up until Christmas Eve, after a spectacular 1941 season. His 218 hits led all of baseball, including legendary seasons by Ted Williams (who batted .406) and Joe DiMaggio, who hit in 56 straight games. When Travis does put on the Army uniform, he spends a large chunk of the war playing baseball stateside. However, he was later assigned to the 76th Infantry Division which participated in the Battle of the Bulge during its 107 days of combat. He earns a Bronze Star and developed a serious enough case of frostbite while fighting in Germany that he required surgery to save his toes.

Travis returned to the Washington lineup in time to play 15 games in 1945, but he clearly wasn’t the same player after the war. Hitting over .300 in eight of his first nine seasons, he only managed .241 in 1945, .252 in 1946, and .216 in 1947. Just before his retirement, Washington celebrated “Cecil Travis Night” on Aug. 15, 1947, with former Allied Supreme Commander Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower in attendance, the Senators presenting Travis with a car and a Hereford bull (Travis was a farmer back home in Georgia).

Buddy Lewis — Travis’ roommate on road trips — would join the Army after his 1941 season. Initially assigned to an armored unit, he received orders for pilot training the day he was supposed to ship out for North Africa. But before the ballplayer-turned-pilot went overseas, he buzzed Griffith Stadium during a game to say goodbye to his team.

Selected for the 1st Air Commando Group, Lewis towed gliders, ferried wounded, and carried supplies on daring missions behind Japanese lines with his C-47 transport in the China-Burma-India Theater, where he would occasionally run into Hank Greenberg. “Everybody agreed he was the best transport pilot in the CBI theater,” said Luke Sewell,1Several sources attribute the quote to the St. Louis Browns manager named Luke Sewell, but considering he managed the Senators throughout the war, it might be incorrect. who flew with Lewis in Burma. “He set his big transport plane down on tiny strips that didn’t look big enough for a mosquito to land on. And he did it while he was talking baseball to me.”

Earning the Distinguished Flying Cross and a couple Air Medals during his nearly 400 combat missions, Lewis had a strong performance when he returned to the diamond in 1945. Although he posted good numbers again in 1946, earning his second All-Star appearance, the now-white-haired Lewis wasn’t the same either and his career began to fizzle out in 1947.

The above quote comes from Lewis’ Washington Post obituary which they attributed to Luke Sewell, who retired as a catcher in 1941 and went on to manage the St. Louis Browns for the duration of the war. It’s possible that the quote belongs to someone else (I will refrain from referring to the Post‘s now-troubled relationship with the truth, considering this is a baseball obituary from ten years ago), such as one of Luke’s brothers, Tommy and Joe, or cousin Rip who also played.

Joe Sewell is a member of the Hall of Fame and was the hardest batter to strike out in baseball history. Luke Sewell struck out three times in his seven plate appearances in 1921. Joe also struck out three times, in 1930 and 1932. But it took him 414 and 576 plate appearances, respectively, to reach his brother’s rookie mark. In his 14 season career, Joe fanned just 114 times. There are probably players today that have struck out more than that before the All-Star break.

(Note: if you click on the strikeout record link, it is a different Chris Carter that holds the record for most strikeouts by a right-hander. I was a switch-hitter, and I can only remember striking out three times, but Baseball Reference doesn’t track Little League or softball)

In 1932 Joe struck out just once every 167.7 plate appearances, which is one record that is probably safe for a very, very long time. While that is certainly impressive, it is worth noting that brother Tommy never struck out. To be fair, he only had one plate appearance, pinch-hitting for the Cubs on June 21, 1927.

Not only was Joe consistent at the plate, he was consistently healthy, or at least consistently present: before Lou Gehrig was baseball’s “Iron Man” for his record 2,130 consecutive games (since broken by Cal Ripken Jr.), Joe had compiled 1,103 straight games, which was then-second-only to Everett “Trolley Wire” Scott. And baseball wasn’t Joe’s only sport: he played varsity football and baseball for the Crimson Tide, while attending classes at the University of Alabama to become a doctor.

And the last fun fact regarding Joe Sewell is that he used the same 40-ounce bat for his entire career. He kept “Black Betsy” in shape by rubbing it with a Coca-Cola bottle and seasoned it with chewing tobacco. This is not to be confused with “Shoeless” Joe Jackson’s famous tobacco-seasoned bat named Black Betsy, which is 48 ounces.

Cousin Rip was a pitcher for the Pirates. His career started out with the Detroit Tigers, but after a fight with Hank Greenberg, he camped out in the minors for five years. The 31-year old Sewell finally got called back to the big show in 1938, and he went on to win 15 or more games four times thanks to his “eephus” pitch, which we discuss in this piece.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 18 April 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-04-18/ed-1/