World War II Chronicle: November 30, 1941

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Page three of today’s newspaper shows soldiers of the 15th “Can Do” Infantry Regiment conducting mountain warfare training. Army Chief of Staff Gen. George Marshall served as the regiment’s executive officer from 1924-1927, while the unit was stationed in China. Lt. Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower led the regiment’s 1st Battalion in 1940…

If you’ve ever wondered where our National Weather Service got its start, you’d have to look all the way back to the Ulysses S. Grant administration. In 1870 the president signed a bill authorizing a weather bureau, which was assigned to the Army’s Signal Service under the name “The Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce.”

Moving ahead to 1941, the Weather Bureau is now a civilian enterprise and, with convoys crossing the globe loaded with cargo essential to the survival of democracy, its job of collecting weather data and issuing reports has never been more important. Before the war, ships of all nations broadcasted weather reports, but now not only are Axis nations not cooperating with the Allies, ships operate under radio silence.

If there is a storm, ships find out the hard way and so do those on shore. Page 45 explains how weather data was collected and disseminated in 1941…

In Tokyo Bay, the 1st Air Fleet’s “Midway Neutralization Unit” — the Fubuki-class destroyers Akebono, Sazanami, and Ushio, accompanied by fleet oiler Shiriya — departs for Midway. A damaged propeller forces Akebono to return for repairs, leaving the task force with just two destroyers. The ships have until Dec. 7 to make the 2,200-mile trip as shelling operations at Midway will commence once Pearl Harbor is attacked. The destroyers carried three dual-mount 12.7 cm/50 Type 3 naval guns (total of six apiece) which could fire a 51-lb. high explosive round over 20,000 yards (9.9 nautical miles).

Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Donald Curtis’ 1st Battalion, 4th Marines have safely reached the Philippines, disembarking at Olangapo. The liner President Mason steams for Singapore after dropping off the Marines. Meanwhile, U.S. forces are still sailing south from China: the typhoon hasn’t managed to sink Rear Adm. William A. Glassford’s Yangtze Patrol gunboats Luzon (PR-7) and Oahu (PR-6), who link up with submarine rescue vessel Pigeon (ASR-6) and minesweeper Finch (AM-9) on this date.

Storms weren’t the only threat to the shallow-water vessels and their meagerly armed escort: tomorrow morning (Dec. 1, 1941) a Japanese seaplane begins circling the American ships. Soon, a Japanese fleet encircles the gunboats and troops aboard a transport use the American ships for target practice. The tense harassment continues until the Japanese break off that evening, likely headed for their assault on Malaya….

From the perspective of an American, 80 years later, it’s difficult to understand the mindset of a Japanese fighting man, joyfully preparing for war with a largely unsuspecting enemy.

Global domination, brutality, and surprise attacks are certainly not unique to 20th Century Japan. One of the reasons the second world war is so popular and thoroughly studied is because it is very personal to so many people. The conquests of the Roman or Mongol Empires were so long ago that it’s hard to have any kind of understanding or connection with those who suffered at the hands of — or carried out the orders of — caesars and khans. History has eroded the memories of both victims and victors to numbers and dates, if we even have that.

But what American today doesn’t know a relative that was directly affected by — or perhaps fought — the Japanese? World War II cuts close.

Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany are mankind’s two most-recent examples of empires seeking to dominate as much of the planet as their strength permitted. Again, nothing new. But in Japan’s case, you had soldiers, sailors, and airmen proud and excited to kill Americans as they slept or were perhaps attending church. Their only beef with the United States was that our Navy could oppose their strategy of conquest. That was clearly enough motivation for young men to taunt and harass Americans prior to December 7 and cheer once they learned the Kudo Butai sailed east to strike Hawaii.

Soldiers knew they could get away with brazenly shooting at our ships because they wanted war and we wanted peace. They were also sufficiently motivated to ruthlessly kill thousands of Americans once the ruse of diplomatic peace process ruse had served its purpose.

Did individual Japanese have reservations or sympathy for those they were about to cut down in coordinated surprise attacks across the Pacific? Certainly some did. And it’s not like we are necessarily better than a Japanese soldier or sailor during World War II; if we were brought up in early 20th Century Japan, the vast majority of us would be behaving just as they did.

The bottom line is that it’s hard to understand a person who cheerfully looks forward to killing someone whose only offense is their ability to check your country’s ambition to conquer.

Page 44 explains what it is like to travel faster than a bullet… Summary of the war’s 117th week on page 44… Sports section begins on page 54, which has more on yesterday’s Army-Navy Game

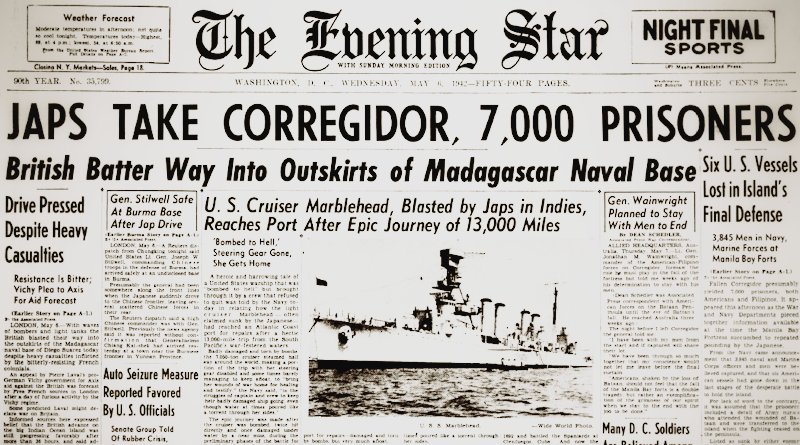

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 30 November 1941. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1941-11-30/ed-1/