World War II Chronicle: January 29, 1942

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

2nd Lt. Alexander R. Nininger Jr. has posthumously earned the Medal of Honor on the Philippines (story begins on page two)… War Department communique no. 81 on page FOUR… Maj. Gen. Frederick Martin, former chief of the Hawaiian Air Force who was removed following the attack on Pearl Harbor, is now in commanding Second Air Force (see page eight)… George Fielding Eliot column on page 13… Sports section begins on page 39

The submarine menace

Most Americans alive today were born in a time where American naval supremacy was essentially a birthright. Other than the occasional intercept of a Cold War-throwback Russian bomber, we take the security of our coastlines — maybe even our hemisphere — for granted.

But that wasn’t the case in January 1942. Enemy submarines prowled our Atlantic, Pacific, and Gulf of Mexico coastlines, and newspapers featured near-daily stories of Americans lost at sea. Page 18 tells the fate of the cargo ship Prusa, torpedoed by the Japanese submarine I-172 south of Hawaii on Dec. 19, 1941. The crew miraculously survived 31 days on the open ocean before reaching the Gilbert Islands.

History tends to focus on the various battles of World War II, but making sure materials got where they were needed was every bit as important to the war effort. That job fell to the brave men of the Merchant Marine, who routinely sailed through waters infested by German and Japanese submarines. When you remember the heroes that fought, bear in mind that 1 out of every 26 men in the Merchant Marine lost their lives — the highest percentage of any service.

On Jan. 19, about 200 miles off the North Carolina coast, the German U-boat U-66 (Korvettenkapitän Richard Zapp, commanding) puts two torpedoes into the Canadian steam passenger ship Lady Hawkins. The attack was so sudden and effective that the liner couldn’t even send a distress call, and the vessel slips under the waves within 30 minutes. After five days at sea, one lifeboat is rescued by an Army transport. Of the 322 crew and passengers, only 71 survive — including 17 Americans.

This attack came just 24 hours after U-66 sank the Allan Jackson, an American freighter carrying 72,000 barrels of oil from Colombia to New York. Zapp’s torpedoes broke the vessel in two and set the oil on fire, burning several shipwrecked Americans alive. A U.S. Navy destroyer was on hand within four hours to rescue survivors. Of the 35 Merchant Marine crew, all but three officers and ten men perished.

For more on the U-boat threat see pages 4, 6, and 10.

Forget Pearl Harbor?

Collier’s magazine war correspondent Quentin Reynolds advised Americans that the slogan “Remember Pearl Harbor” was terribly defeatist and should not be used (page ten).

He justifies his position by pointing out that the British do not use Dunkirk as a rallying cry. So? The surprise attack at Pearl Harbor and the British retreat/rescue operation at Dunkirk share little in common.

Reynolds adds that American warplanes and armor — said to be inferior to their Axis counterparts — have fared quite well in the North African and European theaters in Allied hands. True, aircraft like the P-36 Hawk and Brewster F2A Buffalo were quickly sidelined in favor of more capable Warhawks and Wildcats here in the United States, but French, Finnish, Dutch, and British Commonwealth pilots downed plenty of German and Japanese flyers with their outclassed fighters.

It’s not necessarily that foreign pilots are more capable than ours, or that our pilots were whiny; it very likely comes down to the fact that when your homeland is being invaded and your family is threatened, you fight the best you can with what is available. For Americans, the front lines were thousands of miles away and we had time to produce planes that gave our pilots the best edge possible for facing cutting-edge Messerschmitt, Focke-Wulfe, and Mitsubishi platforms.

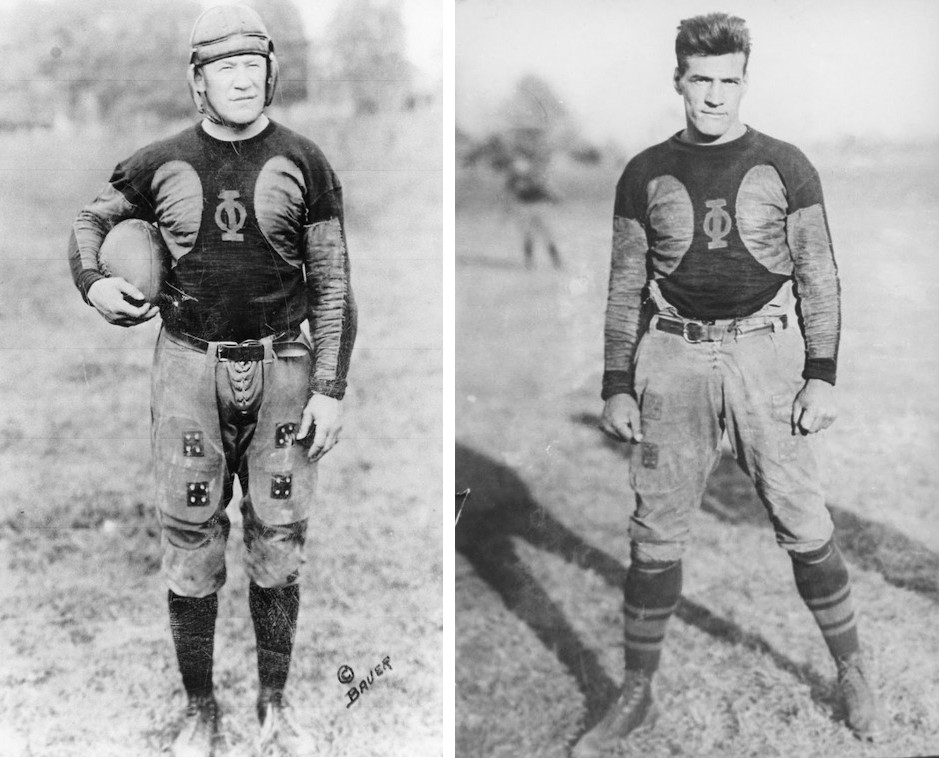

In today’s sports section, Joe Guyon Jr. is reportedly about to become the Navy’s first Native American aviator. His father Joe Sr., a Chippewa Indian, played high school football with the legendary Jim Thorpe (featured image). Thorpe later played for Carlisle Indian Industrial School, who in 1912 beat a West Point club featuring a linebacker named Dwight D. Eisenhower 27-6. Thorpe and Eisenhower also played baseball against each other. Guyon went on to be the starting halfback for Georgia Tech’s 1917 national championship club that went undefeated, outscoring opponents 491-17. Guyon and Thorpe played together several years during their NFL careers, including two seasons with the Oorang Indians, which consisted entirely of Native American players.

Football wasn’t their only sport: Guyon played several seasons of minor league baseball, and Thorpe played six seasons in the big leagues. Both Guyon and Thorpe are in the collegiate and professional football halls of fame. Speaking of athletes and future generals, Jim Thorpe was on the 1912 U.S. Olympic team with George S. Patton. Thorpe took gold in the pentathlon and decathlon, while Patton finished fifth in the modern pentathlon.

Yesterday we mentioned the Boston awards ceremony that Ted Williams had to miss due to his pending induction into the Army. The event is mentioned again today, with Boston general manager and Hall of Famer Eddie Collins accepting the award on Williams’ behalf. Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack called Collins “the greatest second baseman who ever lived,” and also coached his son, Eddie Collins Jr., for three seasons before Eddie Jr. joined the Navy. The younger Collins served as a communications officer aboard the cruiser USS Miami, seeing action in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Okinawa, and Iwo Jima. Joe DiMaggio was also presented with an award, having just set his legendary 56-game hitting streak. DiMaggio will join the Army in February 1943.

Gold wristwatches were awarded to two Hughs: Hugh Duffy, Boston Red Sox scout and soon-to-be Hall of Famer (having set the National League record batting average at .440 in 1894), and Hugh “Losing Pitcher” Mulcahey, who in 1941 became the first baseball player drafted into service.

After an All-Star performance for the basement-dwelling Philadelphia Phillies, Mulcahey was drafted on 8 March, joining the 101st Field Artillery Battalion. He was released on 5 December when draftees over the age of 28 were allowed to return to civilian life. Two days later, Pearl Harbor was attacked and Mulcahey was back in uniform.

It is worth noting that in his 1940 campaign, Mulcahy lost a league-leading 22 games, but this is completely understandable given that the Phillies finished 50 games behind first-place Cincinnati and 15.5 games behind the seventh-place Boston Bees. Philadelphia had just two pitchers on the roster that won more than five games in 1940: Mulcahy (13) and Kirby Higbe (14). Fortunately for Higbe, he was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers during the offseason and won a league-leading 22 games in 1941. Higbe would join the Army after the 1943 season and initially served as a guard. He then was sent to infantry training and became a rifleman for the 86th Division, fighting across Germany and into Austria. After Germany surrendered, the division deployed to the Philippines, arriving as soon as Japan surrendered.

Incidentally, the Chicago Blackhawks hockey team owes its name to the 86th “Black Hawk” Division — named after the Sauk chief who led Native American forces during the Black Hawk War of 1832. Maj. Frederic McLaughlin, who commanded the 86th’s 333rd Machine Gun Battalion during the First World War, bought the Chicago expansion team in 1926 and named the franchise after his former division.

In January 1946, Mulcahy served as an instructor for a baseball camp established by Bob Feller for military veterans returning to baseball. After losing five seasons to the war and 35 lbs. to malaria, Mulcahy only managed to pitch in 23 games over the next three seasons and became a pitching coach and scout for the White Sox.

“I never think back on what might have been,” Mulcahy said about his seasons lost to military service. “I’m very thankful that I came back.”