World War II Chronicle: December 19, 1942

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

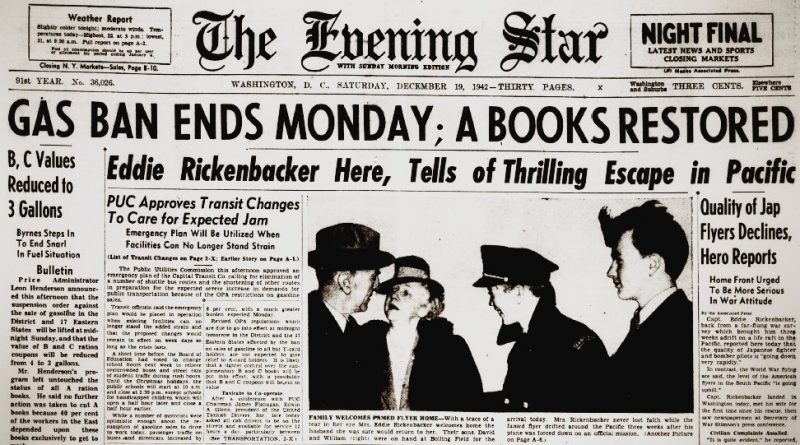

Eddie Rickenbacker has made it back to Washington and is pictured with family on the front page. Both of his sons will enter military service: oldest David joins the Marines in 1943 and Bill enters the Air Force after college and flies transports during the Korean War…

With Rickenbacker is his business partner, Danish-born writer and B-17 pilot Capt. Hans Christian Adamson. He publishes a biography of Rickenbacker after the war. Christmas now just one week away here is the Utility Squadron 7’s Christmas card which is seen on page three… The next page features a story of the Office of War Information’s “request” that Hollywood movie scripts be checked by the government. That seems eerie: something that you’d be more likely to see happen in an Orwellian 2022 than a patriotic 1942…

Lt. Col. John S. Chennault, one of Brig. Gen. Claire Chennault’s five sons to serve in during the war, is pictured on page three… Speaking of pilots, 12 Eagle Squadron pilots are pictured on page four as they have transferred from the Royal Air Force to the U.S. Army Air Force.

Pictured above are several former Eagle Squadron pilots, assembled in a finished wing of the Pentagon, which is still under construction. Some of these pilots wear the RAF’s Distinguished Flying Cross, and although none had received flight training in the United States, they were able to retain their prized British wings. 71, 121, and 133 Eagle Squadrons stayed intact and are renamed the 334th, 335th and 336th. They also keep flying Mk. V Spitfires — now in American colors — until switching to P-47s in April.

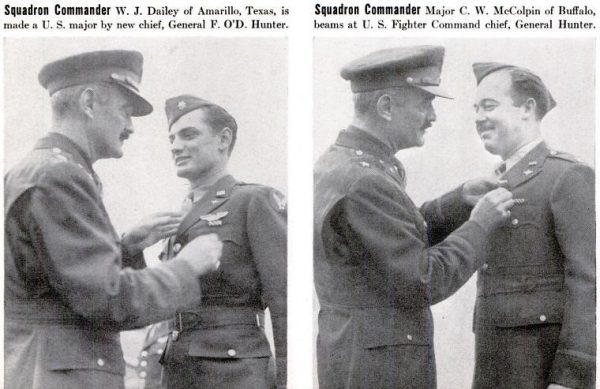

The squadrons form the 4th Fighter Group, currently commanded by Col. Edward W. Anderson. Donald M.J. Blakeslee is picked as the 335th’s commander, and the other squadron leaders are pictured below. Chesley G. Peterson, who led No. 71 Squadron, is now the 4th’s executive officer. When Anderson moves on to another command, Peterson replaces him as the 4th’s commanding officer. Blakeslee takes over the role in 1944.

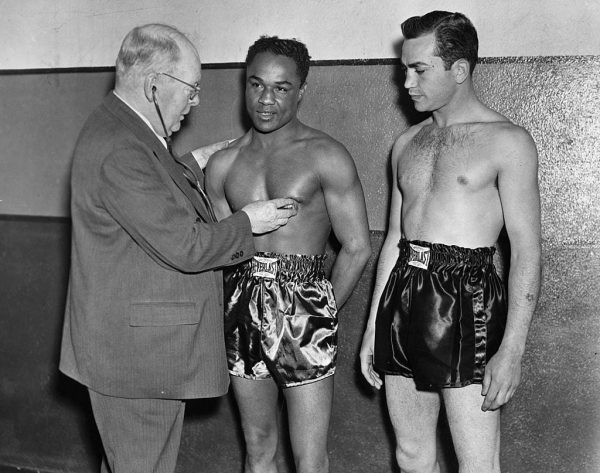

Pinning American wings on former Eagle Squadron pilots above is VIII Fighter Command skipper Brig. Gen. Frank O’Driscoll Hunter. He shot down two German warplanes on his first mission of World War I, and went on to become an ace. His five Distinguished Service Crosses is second only to Rickenbacker. Hunter Army Air Field (near Savannah, Ga.) is named in his honor. George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… Sports section begins on page 12, which mentions the top sports comebacks of the year. Henry Armstrong, who once held the world featherweight, lightweight and welterweight championship titles simultaneously, has won 18 fights since coming out of retirement. Armstrong, now ranked one of the top boxers of all-time, took the welterweight championship from Barney Ross, who is now a Marine private first class fighting on Guadalcanal.

Also recognized is 34-year-old Brooklyn Dodger pitcher Larry French, who has revived his career by learning to throw the knuckleball. He went from a 5-14 record and 4.63 ERA last year with the Chicago Cubs to a 15-4 record with a 1.63 ERA. He currently sits at 197 career wins, and we have not heard from Larry French.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

WITH THE AMERICAN FORCES IN ALGERIA — It’s a terrific task to organize a shipful of troops. It was not until our England-Africa convoy had been at sea nearly a week that everything got settled down and running completely smoothly. An Air Forces colonel was appointing commanding officer of troops on board. An orderly-room was set up, aides were picked, deck officers appointed, and ship’s regulations mimeogrphed and distributed.

The troops were warned about smoking or using flashlights on deck at night, and against throwing cigarettes or orange peels overboard. It seems a sub commander can spot a convoy, hours after it has passed, by such floating debris.

The warning didn’t seem to make much impression at first. Soldiers threw stuff overboard, and one night a nurse came on deck with a brilliant flashlight guiding her. An officer near me screamed at her. He yelled so loudly and so viciously that I thought at first he was doing it for fun. He bellowed:

“Put out that light, you blankety blank-blank! Haven’t you got any sense at all?”

Then suddenly I realized he meant every word of it, and I realized that one little light might have killed us all, and I was sorry he didn’t kick her pants for good measure.

The ship, of course, was entirely blacked out. All entrances to the deck were shielded with two sets of heavy curtains. All ports were painted black and were ordered kept closed, but some people did open them in the daytime.

In the holds below, the ports were opened for short periods each day, to air the ship out. The theory of keeping most of them closed in daytime is that if a torpedo hits with the ports open, enough water could rush in to sink her immediately if she listed.

Everybody had a life preserver, and had to carry it constantly. They were of a new type, rather like two small pillows tied together. You put your head between them, pulled them down over your shoulders and chest, and tied them there. We merely slung them over our shoulders for carrying. They were immediately nicknamed “sandbags.”

After the second day we were ordered to wear our Web pistol belts, with water canteens attached. Even going to the dining room, you had to take your life preserver and your water canteen.

There were nine in our special little group. We were officially assigned together, and we stuck together throughout the trip. We were: Bill Lang, of Time and Life; Red Mueller, of News-Week, Joe Liebling, of the New Yorker; Ollie Stewart, of the Baltimore Afro-American; Sgt. Bob Neville, correspondent for the Army papers Yank and Stars & Stripes; two Army censors, Lts. Henry Mayer and Cortland Gillett, and myself.

Sergeant Neville, being an enlisted man, wasn’t permitted to share cabin space with us, but had to go to general quarters in the hold and sleep in a hammock. We did manage to get him up to better quarters after a couple of days.

Neville was probably the most experienced and traveled of all of us — he speaks three languages, was foreign news editor of Time for three years, has worked for the Herald-Tribune and PM, was in Spain for that war, in Poland for that one, in Cairo for the first Wavell push, and in India and China and Australia.

But he turned down a commission and went into the ranks, and consequently he has to sleep on floors, stand for hours in mess lines, and stay off certain decks. It seems all wrong.

Ollie Stewart is a negro, the only American negro correspondent accredited to the European theater. He is well-educated, conducts himself well, and has traveled quite a bit in foreign countries.

We all grew to like him very much on the trip. He lived in one of the two cabins with us, played handball on deck with the officers, everybody was friendly to him, and there was no “problem.”

We correspondents already knew a lot of the officers and men aboard, so we roamed the ship continuously and had many friends. Bill Lang and I shared a cabin with two lieutenants. We enjoyed ourselves on the trip.

We;d get out the regulations about the correspondents, which say that we must be treated with “courtesy and consideration” by the Army. We’d read these rules aloud to Lieutenants Meyer and Gillett, and then order them to light our cigarettes and shine our shoes. Humor runs pretty thin on a long convoy trip.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 19 December 1942. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1942-12-19/ed-1/