World War II Chronicle: December 18, 1942

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

With Christmas now just one week away here is the Utility Squadron 7’s Christmas card which is seen on page three…

Also on page three, a “cult” leader is on trial for failing to register with Selective Services. You may not have heard of Gulam Bogans, who also goes by Elijah Poole, Muck Muck, Mohammed Rassoull, and about a dozen other aliases, but you might be familiar with Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. He stays in prison until 1946 and continues to lead the group until his death in 1975, mentoring Malcolm X and Louis Farakhan…

Eddie Rickenbacker is back in the United States, but is under orders not to talk about his mission until after he reports to Washington, D.C. (see page four)… On page seven, Marine Corps Barracks New River has been officially renamed after the recently departed Marine general John Lejeune… Sports section begins on page 50

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

WITH THE AMERICAN FORCES IN ALGERIA. — After two days of loading American soldiers aboard our troopship and of hoisting aboard thousands of bedrolls and barracks bags, at last we sailed.

It was a miserable English day, cold with a driving rain. Too miserable to be out on deck to watch the pier slide away. Most of us just lay in our bunks, indifferent even to the traditional last glance at land. Now it was all up to God — and the British navy.

Our ship carried thousands of officers and men and a number of Army nurses. I felt a little kinship with our vessel, for I’d seen it tied up under peculiar circumstances in Panama two years ago. I never dreamed then that some day I’d be sailing to Africa on it.

The officers and nurses were assigned to the regular cabins used by passengers in peacetime. But all the soldiers were quartered below decks, in the holds. The ship had once been a refrigerator ship and now all the large produce-carrying compartments were cleared out and packed with men.

Each compartment was filled with long wooden tables, with benches at each side. The men ate at these tables, and at night slept in white canvas hammocks slung from hooks just above the tables.

It seemed terribly crowded and some complained bitterly of the food and didn’t eat for days. Yet many of the boys said it was swell compared to the way they came over from home to Britain.

Sometimes I ate below with the troops and I’ll have to say that their food was as good as ours in the officers’ mess and that was excellent. Some crowding is unavoidable. It’s bad, but I don’t know how else you’d get enough men anywhere fast enough.

The worst trouble was a lack of hot water. British standards of sanitation are so different from ours that the contrast is sometimes shocking. It took days of scrubbing with sand to get the kitchens and toilets halfway clean.

The water for washing dishes was only tepid and there was no soap. As a result the dishes got greasy and some troops got a mild dysentery from it. The American Army officers, much to their credit, continued to raise so much hell about the ship that by the time we left it things were in much better shape.

In our cabins we had water only twice a day — 7 to 9 in the morning, and 5:30 to 6:30 in the evening. It was unheated, so we shaved in cold water. The troops too lukewarm salt-water showers, by Army order, every three days.

The enlisted men were allowed to go anywhere on deck they wished, except for a small portion of one deck set aside for officers. Theoretically the officers weren’t permitted on the enlisted men’s deck, but that soon broke down. We correspondents could go anywhere we pleased, being gifted and chosen characters.

Instructions for “battle stations” in case of attack were issued. All officers had to stay in their cabins, all soldiers had to stay below. Troops in the two bottom decks, down by the water line, were to move up to the next two decks above them.

Only we correspondents knew where we were going. Some of the officers knew too, and the rest could guess. But an amazing number of soldiers had no idea where they were bound.

Some thought we were going to Russia over the Murmansk route. Some thought it was Norway. Some thought it was Iceland. A few sincerely believed that we were returning to America. It wasn’t until the fifth day out, when the Army distributed advice booklets on how to conduct ourselves in North Africa, that everybody knew where we were going.

The first couple of days at sea we seemed to mill around without a purpose. Eventually we stopped completely and lay at anchor for a day.

Finally we rendezvoused with other ships and then at dusk — five days after leaving London — we steamed slowly into a prearranged formation, like floating pieces of a puzzle drifting together to form a picture. By dark we were rolling and the first weak ones were getting sick at their tummies.

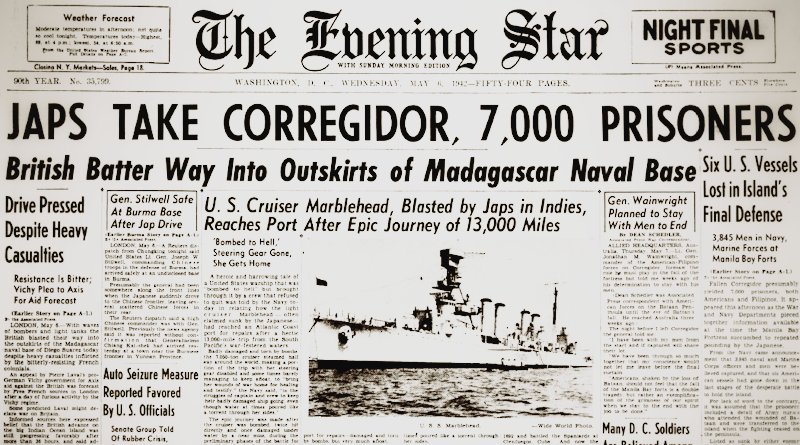

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 18 December 1942. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1942-12-18/ed-1/