World War II Chronicle: June 1, 1943

George Fielding Eliot column on page 10… Sports section begins on page 14. Detroit Tiger phenom left fielder Dick Wakefield is pictured on the following page, and his draft status has been upgraded from 3-A to 1-A. Wakefield received a massive bonus of over $50,000 when he signed with the Tigers, which when adding his yearly salary, he is making more than Hank Greenberg. Wakefield will be drafted next year, after he feasts on wartime pitching. He leads the league in 1943 with 38 doubles and 200 hits, making the All-Star team. Midway through the 1944 campaign he is called up and begins training as a Naval aviation cadet…

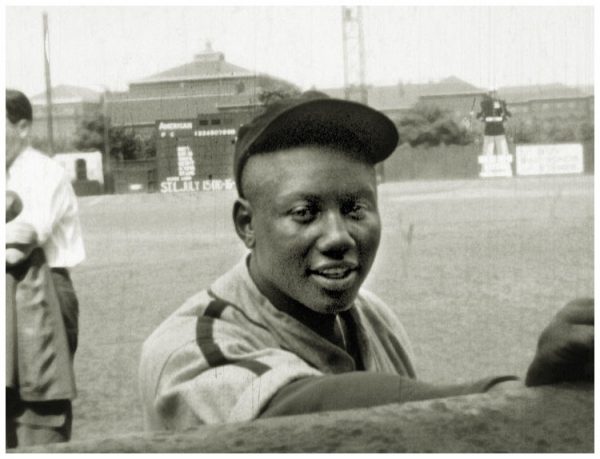

The Negro League’s Washington Homestead Greys are also mentioned on page 15, hard-hitting Josh Gibson blasted two home runs — one a grand slam. Supposedly Gibson hits more home runs at Griffith Stadium this year than the entire American League. This seems unlikely, but Washington’s opponents hit just 14 home runs this year at Griffith. Gibson batted 20, but Negro League statistics don’t differentiate between home and away numbers. The Grays also split their home games between Griffith and Forbes Field in Pittsburgh, so it would be hard to determine if Gibson did outhit the American League. But the fact that we have to look closely to determine if it’s possible is darned impressive.

How good was Gibson? He led the Negro National League in hits, runs, doubles, home runs, runs batted in, walks, on-base percentage, and slugging. He hit 20 home runs and knocked in 109 RBI in just 69 games. If Gibson had played in as many games as Dick Wakefield — 155 — he would have 267 hits, 46 home runs, 50 doubles, and 251 RBI. Now I imagine there are too many variables when comparing Major League and Negro League players to get an accurate comparison. Whether or not Gibson would have fared as well if we magically transported him into the Major Leagues is a question for people who know far more than I do about baseball, but he was an incredibly gifted athlete and it is a damn shame we are left having to speculate because of his skin color…

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

ALLIED HEADQUARTERS, North Africa (By Wireless) — The nicest American camp I’ve ever seen in the fighting area of North Africa is one inhabited by about a hundred men who run the smoke-screen department around a big port to help confuse German air raiders.

I happened upon the thing wholly by accident. Another correspondent and I were driving through country that was strange to us. We came to a town late one afternoon, and were told by a bored billeting clerk that there was no place in town for us to stop and that’s that. So we just said phooey on you, friend, we haven’t slept under a roof in two months anyhow, we carry our own beds with us, and we hate cities to boot.

Whereupon we drove right out of town again and started looking for some spot under a tree where we could camp for the night.

It was during this search that we passed a very neat-looking American camp by the roadside. On an impulse we drove in and asked the first officer we saw if we could just throw our bedrolls down on the ground and stay all night with them.

He said, “What do you want to throw them on the ground for?”

We said “Well we don’t want to put you to any trouble, and we’re accustomed . . .”

“Nonsense!” he said. “We’ll make room for you in our cabins. Have you had supper yet?”

“No, but we’ve got our own rations with us.”

“Nonsense!” he said. “Come and eat first, then we’ll find you a place to stay.”

The officer was Lieut. Sam Kesner of Dallas, Tex. He was wearing coveralls and a field cap and you couldn’t tell him from a private except for his bars. He went to Texas A&M, and got his chemical engineering degree and his Army commission both on the same day.

Kesner’s boss is Capt. J. Paul Todd, of Clinton, S.C. He was a school teacher before the war. He taught mathematics at Rock Hill, S.C. and Atlanta.Their outfit is a part of the Chemical Warfare Service, but instead of dealing out poisonous gases they deal out harmless smoke that covers up everything when the raiders come over.

By the nature of their business they work all night and sleep all day. They take their various stations in little groups in a big semi-circle around the city, just before dusk, and stay there on the alert till after daylight. At midnight a truck makes the rounds with sandwiches and hot coffee. Captain Todd himself also makes a four-hour tour of the little groups each night, ending about 2 a.m.

Their assignment has been permanent enough to justify their fixing up their camp in a homelike way. They have taken old boards from the dock area and built about three dozen small cabins, sort of like tourist-camp cabins back home. They have board floors, board sidewalls and canvas roofs.

They have built bunks for their bedrolls, hung up mosquito nets, hammered boards together for chairs, made tables, and put little steps and porches in front of their cabin doors. They’ve named their cabins such things as “Iron Mike’s Tavern,” “African Lovers,” “The Village Barn” and “The Opium Den.”

Lieutenant Kesner has a sign hanging outside his door that says “Sixty-five Hundred Miles from Deep in the Heart of Texas.” The heart id drawn instead of spelled out.

Captain Todd has a wife back home named Marigene and a daughter named Paulagene. He left when his daughter was four weeks old. Now she’s a year and a half. But he keeps himself well reminded of them, for tacked on the wall of his cabin are 34 pictures of his wife and baby. He’s the picture-takingest man I ever ran onto.

The hundred men in this camp are just like a clan. They have all been together a long time and they have almost a family pride in what they’re doing and the machinery they’re doing it with.

One of the boys in the kitchen said he’d read this column in The Cleveland Press for years. He is Corp. Edward Dudek of (8322 Vineyard Ave.) Cleveland. I asked him what he did before the war besides read this column, and he said he was a chemical worker. The Army clicked long enough to put him into the chemical service, but then a cog slipped somewhere and now he’s a cook instead of a chemical worker. But I suppose he can make his own fumes when he gets homesick by spilling a little grease on the stove.

We spent a comfortable night with this outfit and tarried around a couple of hours the next morning, just chatting, because everybody was so friendly. Then they gassed us up without our even asking for gas, and we finally left feeling that we’d visited the nearest thing to home since hitting Africa.

Capt. Todd retired from the Army Reserve as a lieutenant colonel in 1974 and passed away in 2009. Lt. Kesner left the service as a major. His parents were immigrants from Russia and Romania, and he departed in 2004.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 1 June 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-06-01/ed-1/