World War II Chronicle: July 8, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

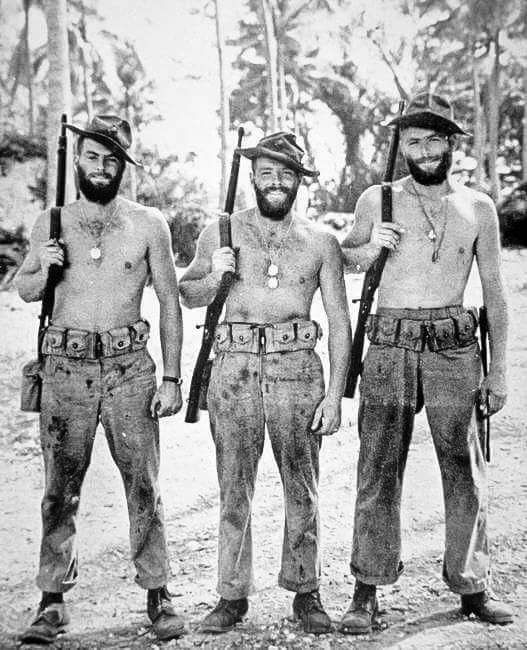

The mortality rate of evacuated soldiers is five times lower than it was in the first world war. According to the Army’s surgeon general, only about three percent of wounded soldiers sent to a hospital perish. He credits getting soldiers into surgery quickly, along with medics administering plasma and sulfa drugs on the front lines… The three Madden brothers of Glendale, Calif. are pictured on the front page. Marine records show Art and Walt are both wounded on June 15, 1944 — most likely during the landing at Saipan. This John is not the famous NFL coach and announcer, who was born in 1936…

Notre Dame Four Horseman “Sleepy Jim” Crowley is pictured in the South Pacific, as is Lt. Col. James Roosevelt who has just transferred command of the 4th Marine Raider Battalion (see page three)… George Fielding Eliot discusses Kursk on page 12…

Sports on page 19, and former Wisconsin Badger Pat Harder will get a break from the action at Parris Island to play in the College All-Star Game against the Washington Redskins. Harder is enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame and won three NFL Championships when he turned pro after the war. He became an official after retiring, and umpired the “Immaculate Reception” playoff game between the Steelers and Raiders in 1972… Another hall of famer is mentioned in another column: Ken Kavanaugh played for LSU and was drafted by the Chicago Bears but is now flying B-17s for the Eighth Air Force. His teammate at both LSU and Chicago is Young Bussey, who threw a touchdown for Chicago during last year’s College All-Star Game and enlisted in the Naval Reserve after the game…

On page 22, the French military commander in North Africa decorated 1st Division commanding general Terry De La Mesa Allen and his assistant Teddy Roosevelt Jr. for conspicuous service.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

NORTH AFRICA — The Red Cross has a few critics but they are few indeed. The wonder is that it gets its job done at all, considering the conditions under which it has to work.

When the Red Cross opens up a new war theater its growth has to be as fast as the growth of the army. The way clubs spring up overnight in newly occupied centers, the way restaurants and dances and movies and clubmobiles and hospital workers mushroom into life all over a new country, is something that still astounds me.

Bill Stevenson, the Red Cross delegate to Africa, wouldn’t admit this himself, but actually his job is to do things for the army in spite of the army. Not that anybody is against the Red Cross. It isn’t that. But the Red Cross has depended on the army for a great many things — for jeeps, and boat priorities, and requisitioned buildings, and permissions of many kinds — and each of these is guarded by some individual whose job is to conserve things for strictly military use. The result is a fine art of wheedling on the part of Mr. Stevenson. But things do get done.

We who have written about the Red Cross in the past have usually centered upon the fine clubs it operates in all the big centers where troops are stationed. And yet actually — and I didn’t know this until a few days ago — the club part comes third in the list of the things the Red Cross has done in Africa.

First and foremost is the hospital program. The Red Cross has women workers with every hospital in this theater — five each at the big ones, three at the smaller ones.

Second is the field program. This is run by men, who hive and work with combat outfits. They dole out books, towels, toilet sets, writing paper — all the little things the soldiers lose in battle. They are horns of plenty and father confessors and Johnny Fixer-Uppers.

They are the ones who wire home to see if Pvt. Joe Smith has become a papa yet. They bring the sad news that a soldier’s mother has died at home. They talk things over and get a neglectful boy to write home.

Through these field workers the soldiers have direct contact with America in cases of family emergency. It’s surprising the number of cases they handle. Every day 250 cables and 300 letters start across the ocean, solving soldier’s problems — it takes seven American girl stenographers typing constantly to keep these messages flowing.

The field men conduct 26,000 interviews a month with soldiers, advising them about allotments and other things.

The most spectacular Red Cross activity, although third on the program, is the club service. Today the Red Cross has more than 40 clubs in North Africa. These aren’t just little reading-room affairs — they’re hotels of four or five stories, serving meals, providing beds, and equipped with snack bars, lounge rooms, dances, and movies. Running all this is in a minor way the same as running an army. It’s a terrifically big business.

The Red Cross has 365 Americans over here now, and 100 more are due shortly. It has hundreds of local employees. Sixty per cent of the Americans are women.

No matter what deep services the Red Cross may perform, Stevenson says it is the touch of femininty that does the soldiers the most good. Despite his metropolitan background Bill has been naive all his life about the influence that women wield in this world. He has found out in Africa.

Bumpy (Mrs. Stevenson) laughs and says that’s the outstanding thing Bill has learned in his war career — he has awakened to the powerful existence of womanhood.

He has found it out in two ways — one, the touching approval and desire of the soldiers for female companionship, even if it consists of nothing more than standing and looking at an American girl behind a counter; and, two, the rather laughable troubles he has with his staff in matters of the heart.

Bill has what he calls “colonel trouble.” It seems his gals are always getting engaged to colonels. You’d think a man old enough to be a full colonel would either be well married and settled or else determined to be an old bachelor. But no. Colonels moon around the Red Cross workers like country swains and the first thing you know they’re betrothed, begorra.

There’s no rule against Red Cross girls getting married while overseas, but there is a rule that they can’t be stationed in the same area as their husbands. One general who has a colonel about to get married on him says he will consent only on condition that they will be stationed a thousand miles apart.

Bill Stevenson wonders whether it’s going to be the General’s duty to keep the colonel-husband away from his wife, or his (Bill’s) duty to keep the Red Cross wife away from her husband. I suggest that Bill and the General make up a pot between them and hire a small Arab boy to stand watch.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 8 July 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-07-08/ed-1/