World War II Chronicle: July 23, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Front page: President Roosevelt is defending his decision to bomb Rome. The Allies requested that Mussolini declare Rome an open city to spare it from damage, but would you want to surrender your capital if you were the fascist dictator of Italy? Sure, the enemy is sweeping across Sicily and in fact today has captured its capital of Palermo (see page two), but there is still a long time before there are enemy soldiers on the mainland, if the Allies do attempt an invasion. And with Axis lines contracting their strength is concentrating…

Page two reports that Maj. Gen. William P. Upshur, Commanding General of the Marine Corps’ Department of the Pacific, has perished in an airplane crash while on an inspection tour in Alaska. Upshur received the Medal of Honor during combat in Haiti. Also killed was Capt. Charley Paddock, who earned the title “fastest man alive” after serving as a field artillery officer during the World War. Paddock won two gold medals in the 1920 Olympics: the 100 meter sprint and the 4 x 100 team relay…

Lt. Gen. George S. Patton is pictured wading ashore on page four, with a caption mentioning the general carried his “pearl-handled revolvers.” Military history buffs will remember Patton saying, and this is an actual quote: “They’re ivory. Only a pimp from a cheap New Orleans whorehouse would carry a pearl-handled pistol.” One of his pistols is the Colt Single Action Army “Peacemaker.” He used this 4-1/2″ barreled .45 in a gunfight with two Pancho Villa lieutenants in 1916 and carried it throughout his career. Patton’s other ivory-handled piece was his .357 Magnum Smith & Wesson (3-1/2″ barrel), but the general carried numerous handguns throughout the war, like a .380 Remington Model 51 automatic…

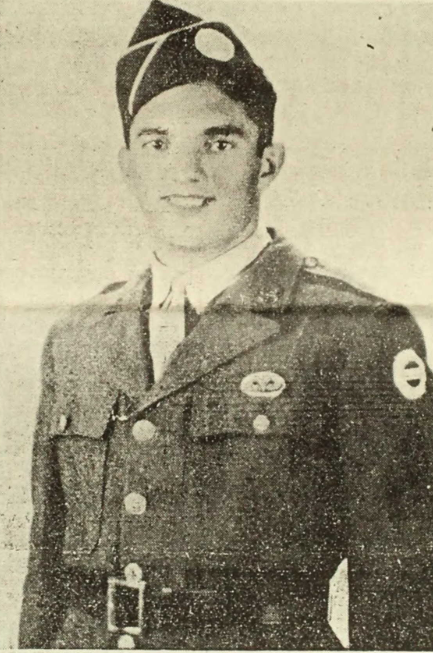

Page six reports that a paratrooper has survived brutal treatment by the Italians, and escaped when they left him for dead. Michael A. Scambelluri was assigned to C Company 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division and has been evacuated to recover in a North African hospital. After being shot multiple times in the chest and surviving grenade blasts — the Italians believed the Italian-American private first class was a spy — the Italians then sunk the hospital ship Scambelluri had been loaded aboard. Stay tuned for more…

Last time we wrote about one-armed Royal Air Force squadron commander J.A.F. MacLachlan he was training RAF pilots at Pensacola, Fla. “One-Armed Mac” had his left arm amputated below the elbow after being shot down by a Luftwaffe pilot in February 1941. He had a prosthetic forearm and hand made that he uses to fly fighters. He was flying two weeks after surgery and returned to combat two months later.

MacLachlan was reported missing yesterday (see page seven) after he and fellow pilot Geoffrey Page flew over occupied France at treetop level to hunt unsuspecting Luftwaffe planes. Both pilots are veterans of the Battle of Britain and Page was burned so badly when he was shot down in 1940 that he required 15 surgeries before he could get back in a cockpit. Flying North American Mk. I Mustangs, the pair shot down six enemy aircraft in 10 minutes on their first sortie into France, but MacLachlan’s luck ran out on the second trip: enemy machinegun fire raked his Mustang and he crash-landed. He is taken into custody by the Germans, who take him to a field hospital. He dies 13 days later, credited with 16 victories and one shared. He earned the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Distinguished Service Order with two bars. His brother Flight Lieutenant Gordon Baird MacLachlan flew Spitfires and also perished when he was shot down over France in April 1943….

Sports on page 12… A ball turret gunner that normally doesn’t wear his parachute in his cramped office is darned glad he tried it his first time over England. The turret’s door opened at about 16,000 feet, suddenly dumping him out. He landed right next to a group of American soldiers, not far from his home base (see page 13).

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

SOUTHERN SICILY — On our first morning in Sicily I stopped to chat with the crew of a big howitzer which had just got dug in and camouflaged. The invasion was only a few hours old but in our sector it was nearly over.

This gun crew was digging foxholes. The ground was hard and it was very tough digging. Our soldiers were mad at the Italians.

“We didn’t even get to fire a shot,” one of them said in real disgust.

Another one said, “They’re gangplank soldiers” — whatever that means.

Their attitude expressed the disappointment of lots of our soldiers. Our troops had been through such keen and exhaustive training they were worked up to a violent pitch and it was an awful let down to find nothing to take it out on.

I talked with one Ranger who had been through Dieppe, El Guettar and other tough battles and he said this was by far the easiest of all. He said it left him jumpy and nervous to get trained to razor-edge and then have the job fizzle out, the poor fellow, and he was sore about it!

This Ranger was Sergeant Murel White, a friendly blond fellow of medium size, from Middleborok, Ky. He has been overseas a year and a half. Back home he has a wife, and a five-year-old daughter. He used to run his uncle’s bar back in Middlesboro and he says when the war is over he’s going back, drink the bar dry, and then just settle down behind it for the rest of his life.

Sergeant White and his commanding officer were in the first wave to hit the shore. A machinegun pillbox was shooting at them and they made up hill for it, about a quarter of a mile away. They used hand grenades.

“Three of them got away,” White said, “but the other three went to Heaven.”

Since the invading soldiers of our section didn’t have much battle to talk about they looked around to see what this new country had to offer and you’d never guess the most commented-upon discovery among the soldiers that first day.

No, it wasn’t signoritas, or beer, or Mount Etna. It was that they found fields of ripe tomatoes! And did they eat them! I heard at least two dozen speak of it during the day as though they’d found gold. Others said they found watermelons too, but I couldn’t find any.

I hitched a ride into the city of Licata with Maj. Charles Monnier, of Dixon, Ill., and Sgt. Earl Glass of Colfax, Ill., and Sgt. Jaspare Toarmina of Brooklyn. They are all engineers.

Toarmina was driving and the other two held tommyguns at ready, looking for snipers. Toarmina himself was so busy looking for snipers that he ran right into a shell-hole in the middle of the street and almost upset our jeep.

Toarmina is of Sicilian descent. In fact his father was born in a town just 20 miles west of Licata and for all he knows his grandmother is still living there. The Sergeant can speak good Italian so he talked to the local people on the streets. They told him they were sick of being starved and browbeaten by the Germans and the reason they put up such a poor show in our sector was that they didn’t want to fight.

They said the Germans had lots of wheat locked in granaries in Licata and they hoped we would unlock the buildings and give them some of it.

Before the sun was two hours high our troops had built prisoner-of-war camps out of barbed wire on the rolling hillsides and all day long groups of soldiers and civilians were marched up the road and into the camps.

At the first camp I came to about 200 Italian soldiers and the same number of civilians were sitting around on the ground inside the wire. There were only two Germans, both officers. They sat apart in one corner, disdainful of the Italians. One had his pants off and his legs were covered with Mercurochrome where he had been scratched. Civilians even brought their goats into the cages with them.

After being investigated those who were harmless would be turned loose. The Italian prisoners seemed anything but downhearted. They munched at biscuits, asked their American guards for matches. As usual, the area immediately became full of stories about prisoners who’d lived 20 years in Brooklyn and who came up grinning asking how things were in dear old Flatbush.

Pyle is writing about Technician Fourth Grade Murel C. Whited, who earns the Silver Star on Sicily. He is serving with 3rd Battalion, 290th Infantry, which is part of the 75th Infantry Division. Later in the war he joins the 1st Special Service Force, a joint American-Canadian special operations unit. Today’s Canadian Special Operations Regiment and the U.S. Army Special Forces trace their lineage back to the Special Service Force.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 23 July 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-07-23/ed-1/