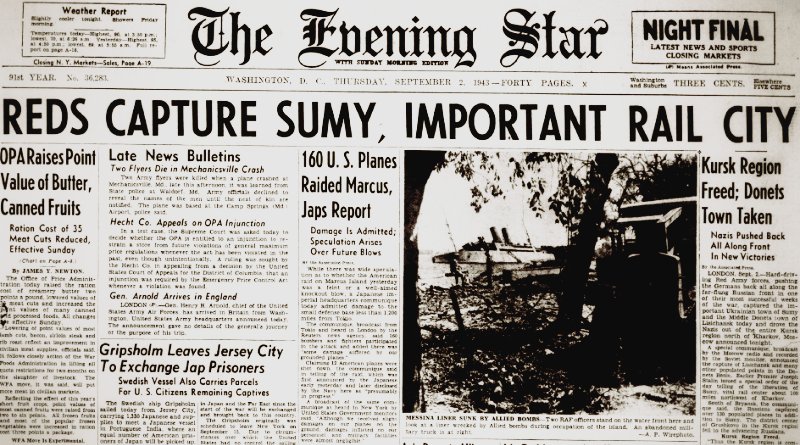

World War II Chronicle: September 2, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

Page three features the story of a ship that was blown in half when a North Atlantic storm blew two depth charges off her rack. Miraculously, all hands were saved. USS Wasmuth began life as a four-stack destroyer in 1921 and was converted to a high-speed minesweeper in 1940…

Page six has yet another example of Japanese pilots are firing on Americans in parachutes… Lt. Gen. George S. Patton awarded Marty Moritz, a medic with the 30th Infantry Regiment. Patton said he has awarded many such awards but no soldier was as deserving as Moritz (story on page nine)… George Fielding Eliot column on page 10…

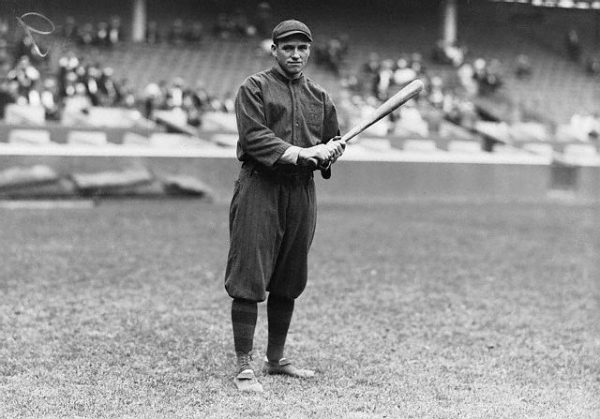

Former Boston Braves slugger Joe Connolly has passed away (page 12). The Woonsocket Evening Call did their announcement with a little better style than the Star: “Joey Connolly Called Out By Great Umpire.” Connolly’s hitting was a large factor in the Miracle Braves’ World Series victory despite being in last place halfway through the season…

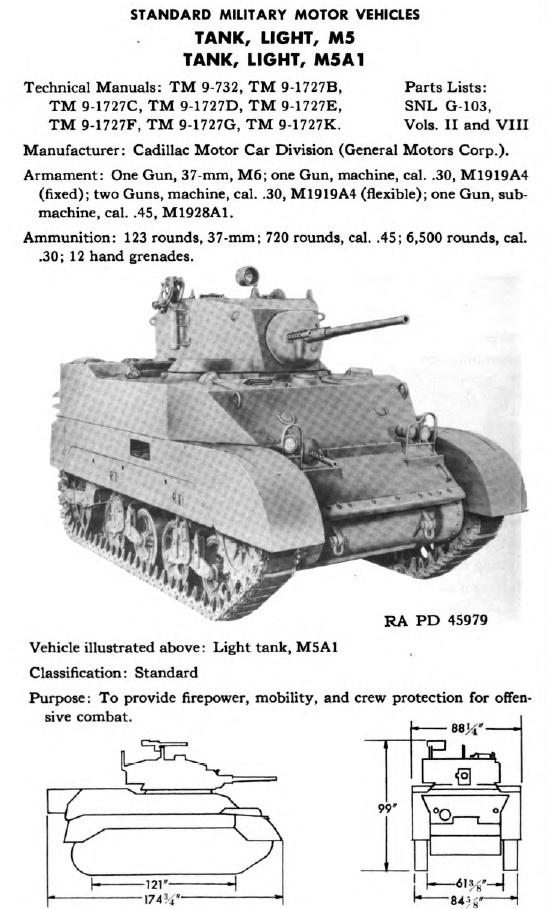

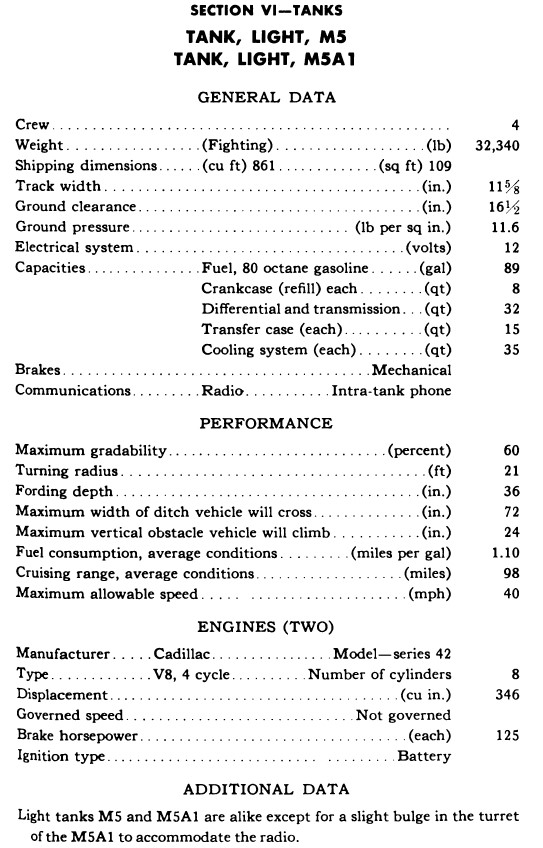

Sports on page 16… The M5 Stuart is pictured on page 18, as is the new M3 “Grease Gun.” The M3 hasn’t entered service yet, but American forces will be using the cheap and effective sub-machine gun for decades. Here are the specs on the Stuart light tank from a training manual released just yesterday:

An American artilleryman recovering at Walter Reed Hospital says that a majority of the German artillery rounds that hit his position were duds and believes that saboteurs in German munitions plants are the cause (story on page 21)… Marine captain Kenneth A. Walsh, whom we just wrote about the other day, has bagged another four Japanese planes, bringing his record to 20 victories. He is assigned to Marine Fighting Squadron 124 (VMF-124) in the Solomons. I’m certainly not excusing the Japanese tactic of shooting at American pilots in parachutes, but Japanese pilots are getting absolutely torn up in the air. Two-thirds of the group sent up to intercept the Marines were blasted out of the sky, and we can read plenty of stories of this being repeated across the Pacific Theater. I don’t know whether or not the situation had become hopeless yet for Japan’s air forces, but I can at least appreciate how desperate their situation must be…

Maj. Henry K. Love served in Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in Cuba. He also served under Colonel Louis A. Craig Jr., father of former Chief of Staff General Malin Craig. And at one point he outranked the current Navy Secretary, Frank Knox. The 81-year-old veteran of three wars is now trying to take a job in the District so he can free someone else up to go and fight. Major Love’s story is on page 22…

Today we conclude the NFL’s All-Decade Team of the 1940s, featuring the guards and centers.

Guards: Stanford’s Bruno Banducci was picked in the sixth round of the 1943 NFL Draft. The Italian immigrant will start his professional career the Philadelphia Eagles next season… Bill “Monk” Edwards played three seasons for the New York Giants before joining the FBI, and then the infantry… Buster Ramsey was the first All-American from the College of William & Mary and was picked in the 14th Round of the 1943 Draft. He is currently in the Navy… Bill Willis was one of very few college football players when he joined Ohio State’s roster in 1941. He will have to wait until after the war to make his pro debut, reuniting with his current coach Paul Brown at Cleveland… New York Giant Len Younce could do it all — he was an offensive lineman, linebacker, kicker, and punter. 1943 will be his second season…

Centers: Green Bay’s Charley Brock has made the Pro Bowl in three of his four seasons… Clyde “Bulldog” Turner has been selected first-team All-Pro twice in his three seasons with the Chicago Bears… Alex Wojciechowicz was one of Fordham University’s “Seven Blocks of Granite.” He was the sixth overall pick of the 1938 NFL Draft and is beginning his sixth season with the Lions.

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

SOMEWHERE IN SICILY — During the latter days of the Sicilian campaign, I spent all my time with the combat engineers of two different divisions.

For months I have been wanting to write about engineers and when I finally got around to it, it seemed as though fate had picked out the time for me — the engineers were in it up to their ears.

Scores of times during the Sicilian fighting I heard the expression voiced by everybody from generals to privates that “This is certainly an engineer’s war.” And it indeed was.

Every foot of our advance upon the gradually withdrawing enemy was tempoed by the speed with which our engineers could open the highways, clear the mines and bypass the blown bridges.

In northeast Sicily, where the mountains are close together and the valleys are steep and narrow, it was an ideal country for withdrawing and the Germans made full use of it.

They blew almost every bridge they crossed. In the American area alone they destroyed around 160 bridges. They mined the by-passes around the bridges, they mined the beaches, they even mined orchards and groves of trees that would be a logical bivouac for our troops.

They didn’t fatally delay us, but they did give themselves time for considerable escaping. The average blown bridge was fairly easy to bypass and we’d have the mines cleared and a rough trail gouged out by a bulldozer within a couple of hours but, now and then, they’d pick a lulu of a spot which would take anywhere up to 24 hours to get around.

And in reading of the work of these engineers you must understand that a 24-hour job over here would take many days in normal construction practice. The mine detector and the bulldozer are the two magic instruments of our engineering. As one sergeant sad, “This has been a bulldozer campaign.”

In Sicily, our Army would have been as helpless without the bulldozer as it would have been without the jeep. The bridges in Sicily were blown much more completely than they were in Tunisia. Back there they’d just drop one span with explosives. But over here they’d blow down the whole damn bridge, from abutment to abutment. They used as high as a thousand pounds of explosives to a charge and on one long, seven-span bridge they blew all seven spans. It was really senseless and the pure waste of the thing outraged our engineers. Knocking down one or two spans would have delayed us just as much as destroying all of them.

The bridges of Sicily are graceful and beautiful old arches of stone or brick-facing, with rubble fill, and shattering them so completely was something like chopping down a shade tree or defacing a church.

They’ll all have to be rebuilt after the war and it’s going to take a lot more money than necessary to replace all those hundreds of spans. But I suppose the Germans and Italians figured dear old Uncle Sam would pay for it all, anyhow, so they might as well have their fun.

Frequently the Germans, by blowing out a road carved out of the side of a sheer cliff, caused us more trouble than by bridge blowing. In these instances, it was often impossible to by-pass at all, so traffic had to be held up until an emergency bridge could be thrown across the gap.

Once in a while you would come to a bridge that hadn’t been blown. Usually that was because the river bed was so flat, and by-passing so easy, it wasn’t worth wasting explosives. Driving across a whole bridge makes you feel funny, almost immortal.

We have one whole bridge the Germans didn’t count on. They had it all prepared for blowing and left one man behind to set off the charge at the last moment. But never got it done. Our advance patrols spotted him and shot the villain dead.

The Germans were even more prodigal with mines here than in Tunisia. Engineers of the 45th Division found one mine field, covering six acres, containing 800 mines. Our losses from mines have been fairly heavy, especially among officers. They scout ahead to survey demolitions, and run into mines before the detecting parties get there.

The enemy hit two high spots in their demolition and mine planting. One was when they dropped a 50-yard strip of cliff-ledge coast road, overhanging the sea, with no possible way of by-passing. The other was when they planted mines along the road that crosses the lava beds in the foothills north of Mount Etna. The metal in the lava threw out the mine detectors helter-skelter, and we had a terrible time finding the mines.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 2 September 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-09-02/ed-1/