World War II Chronicle: September 17, 1943

Click here for TODAY’S NEWSPAPER

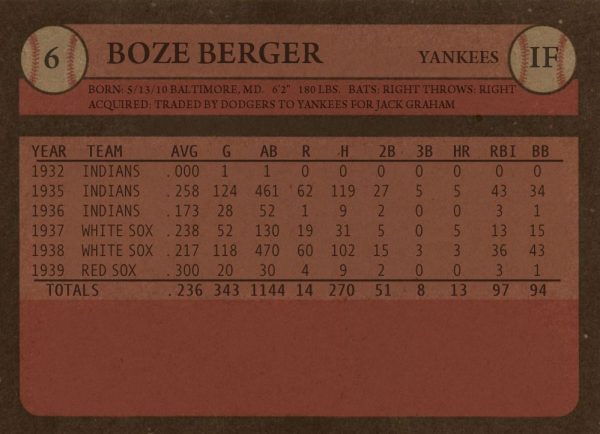

The front page reports that a massive explosion at Norfolk Naval Air Station has claimed the lives of 17 sailors so far. Hundreds are injured from the blast. Stay tuned for more… Meanwhile, the American Fifth and British Eighth Armies are linking up in Southern Italy… On page nine a former baseball player named William “Boze” Berger is mentioned having been promoted to captain in the Army Air Force. Berger was a major in ROTC while at the University of Maryland and served in the Army Reserve during his six big-league seasons. Berger was a “can’t miss” prospect in baseball, but he was an all-around athlete; he was Maryland’s first All-American basketball player and scored two touchdowns in his first college football game. Before the United States entered World War II he coached Fort Myer’s basketball team.

Berger will remain in the service after the war, making a career out of the Air Force… George Fielding Eliot column on page 12… Sports on page 20, and the Yankees and Cardinals may both have their pennants clinched by the end of this weekend. Meanwhile, former St. Louis pitcher Johnny Beazley appeared for Fort Ogelthorpe (Ga.) in Southern Army’s baseball championship series against Second Army… Former fullback Bronco Nagurski will be back with the Bears this weekend to prepare for the first game of the year next weekend…

Also in today’s paper:

- Lae’s Fall Imminent; Allied Flyers Down 48 Planes at Wewak (page five)

- D. C. Doughnut Man Reaches Salamaua Ahead of Troops (page 10)

- Col. Archie Roosevelt Aids Salamaua’s Fall By Bold Gun Charting (page 49)

Roving Reporter by Ernie Pyle

WASHINGTON — John Steinbeck is a recent addition to our corps of war correspondents in the Mediterranean, as you know. He is now with the invasion forces somewhere along the Italian shores.

Some people are speaking of Steinbeck and me as competitors in the field of war columning. I’m flattered by the inference. But there is neither competition nor comparison. It would be belittling Steinbeck’s genius to compare him with any daily deadline-catcher.

I’ve always been a Steinbeck worshiper. For my money, he’s the greatest writer in the world. I think it one of literature’s losses that he never got to England during the blitz, to record the moving spirit of that unrecapturable winter. But while he was missing that he was producing “The Moon is Down,” so maybe it was all right after all.

I’m glad that Steinbeck is at last with the wars. For he carries to them a delicate sympathy for mortal man’s transient nobilities and beastliness that I believe no other writer possesses.

Surely we have no other writer so likely to catch on paper the inner things that most people don’t know about war — the pitiableness of bravery, the vulgarity, the grotesquely warped values, the childlike tenderness in all of us.

I met Steinbeck for the first time in Africa, just after returning from Sicily. He was killing time before starting on the Italian invasion, and I was getting ready to come home.

For some reason I had always been afraid of Steinbeck, even while admiring him. Several times in California I’d passed up the chance to meet him. And there in Africa it was several days before I got up the courage to go around and introduce myself.

And then, as often happens in such cases, Steinbeck turned out to be neither difficult nor blunt. He turned out to be human as hell, friendly, story-telly, laughy and gay. He even admits he’s awfully homesick, though he’s been gone only three months.

He is a big bruiser of a guy who belies the fine edge of sensitiveness within him. He goes around needing a haircut and with his sleeves rolled up, looking almost as unmilitary as I do.

Walk along the streets with him, or ride around the country, and you’ll find his mind constantly pierced and impressed by every little event or scene before him. His consciousness is fertile and always at work. Sometimes he’s serious and sometimes he’s funny and sometimes he’s sardonic. But it’s always himself: he isn’t one of those people who act.

He makes such remarks as, “There’s something about a jeep that brings out the worst in every driver.” And one day we were standing on the curb when a dirty, ragged Arab child ran up and asked for money.

Steinbeck looked down at him a long time with mock gravity, and then he said, “Do you mean to tell me that to your hopeless heritage of malnutrition, ignorance and internecine warfare, you now propose to add the degradation of charity?” The bewildered child turned and ran away.

Steinbeck isn’t dour, or taciturn, as I had somehow gathered from his writing that he would be. He’s willing for anything; you don’t have to do whatever Steinbeck wants to do: he does what the crowd wants to do.

If somebody tells a story he’ll tell one too, and laugh at his own stories like the rest of us humans. Correspondent H.R. Knickerbocker has a good description of him. Knick says, “A lot of these celebrated writers, when you meet them, act as though they might let out some secret of their profession if they opened their mouths. But this guy Steinbeck, hell, he gives forth and keeps on giving.”

I don’t know how long Steinbeck intends to stay abroad. I hope not too long. You don’t have to live with war forever to absorb its basic character. A few months will equip him with all the sight and understanding of war he needs for the production of a great book. He is so alert and aware that he gets something from and contributes something to every little move or word of the day. The war is better for having him in it.

Evening star. (Washington, D.C.), 17 September 1943. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress.

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1943-09-17/ed-1/